The dust is still settling in Washington after last week’s last-minute drama to get President Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” (OBBB) through Congress. For anyone who missed the action, Alaska emerged as the clear state winner, thanks in no small part to a handful of “gimmies” thrown in to persuade Senator Murkowski’s decisive vote, including a niche deduction for Alaska Eskimo whaling captains.

But while much of the recent analysis is focused on tax cut extensions and Trump campaign trail promises such as “no tax on tips,” the real story for states is buried in the 800 plus pages. This bill dramatically reshapes how two key federally funded programs, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid, will be managed, ratcheting up pressure on state budgets across the country.

We have gone through the bill so you don’t have to.

We break down what’s in OBBB and highlight how these changes could impact state leaders, program administrators, and budgets in the years ahead.

What’s Really in the One Big Beautiful Bill?

OBBB is more than just a tax bill, it’s a massive legislative package that will reshape the federal-state relationship for a generation. The new policies for SNAP and Medicaid represent a major lift for states, both in terms of administrative burden and budget pressures. While expanded work requirements and fewer waivers are intended to encourage self-sufficiency, new cost-sharing formulas mean states will now cover a greater share of SNAP and Medicaid costs, with error rates and compliance becoming more critical than ever. Most states will be making tough decisions, and some may even need to call special sessions just to manage the implementation.

But with challenge comes opportunity.

State leaders now have a chance to reimagine these programs so they serve their populations more effectively, preserve benefits for those who truly need them, and help people get back on their feet through work and improved quality of life.

This moment also underscores a hard truth: federal funding is unpredictable, and states must be prepared to protect themselves against future uncertainty. Now is the time to get ready, get involved, and ensure your state is prepared for the changes ahead.

Here’s a quick overview of what’s in the bill that impacts states:

For more details on each section, visit out Center for Practical Federalism.

Table of Contents

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Reforms

Electronic Vehicle and Energy Credits

Medicaid Reforms

Border State and Local Government Assistance

Tax Credit for Education Scholarships

State and Local Tax (SALT) Deduction

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Reforms

Applies to able-bodied adults without dependents aged 18–64 (previously capped at age 54), adults with dependents 14 and over and removes the exemptions for veterans, homeless, and foster children that have “aged-out” of the system. States may no longer gerrymander waiver regions, instead must use standardized Labor Market Areas as defined by Bureau of Labor Statistics. Waivers are allowed only for Alaska and Hawaii if their unemployment is greater than 1.5 times the national average. All existing waivers expire Dec 31, 2028.

Increased Admin Cost Share for States (Section 10106)

Increases state share of SNAP administrative costs from 50% to 75% beginning FY2027.

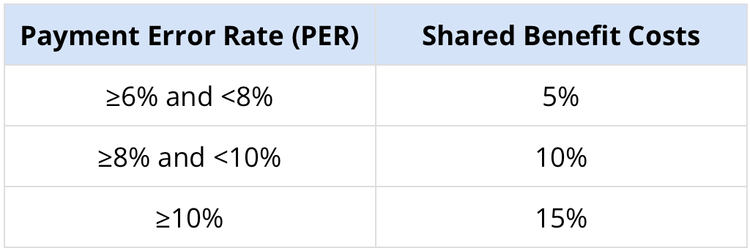

Benefit Cost Share for States based on Error Rates (Section 10105)

Begins in FY2028. States with a SNAP payment error rate (PER) above 6% must share benefit costs:

- States may use FY2025 or FY2026 PER for FY2028; PER from three years prior used in later years.

- States with high PER (FY2025 PER multiplied by 1.5 is equal to or above 20%) have a delayed implementation date of FY2029 or FY2023 if they meet this criteria with FY2026 PER.

- AK and HI may receive a two-year waiver.

- View 2024 error rates: https://fns-prod.azureedge.us/sites/default/files/resource-files/snap-fy24QC-PER.pdf

Other Changes to SNAP:

- Thrifty Food Plan (Section 10101) – Addresses Biden’s 2021 benefit expansion by locking in 2021 Thrifty Food Plan as baseline; future updates only every five years if cost-neutral (starting Oct 1, 2027); annual inflation-based adjustments allowed starting FY2026. Allows regional adjustments for Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, and the Virgin Islands.

- Internet Fees Disallowed (Section 10104) – Internet service fees no longer deductible under excess shelter cost formula.

- Non-Citizen Household Income (Section 10108) – Income of household members ineligible for SNAP due to immigration status must be counted for eligibility determinations.

Electronic Vehicle and Energy Credits

Repeal of Electronic Vehicle Credits (Section 70501, 70502, 70503)

Clean Vehicle Credits for used, new and commercial vehicles end September 30, 2025.

Repeal of Clean Electricity Tax Credits (Section 70512)

Repeals Sections 45Y (Clean Electricity Production Credit) and 48E (Clean Electricity Investment Credit). To qualify for the credits, projects currently under construction must be placed in service on or before December 31, 2027.

Projects can also qualify for the credits if construction begins within 12 months of the enactment of the bill, which requires at least 5% of the project cost to be expended. Credits can still be transferred but with restrictions on transfers to “Prohibited Foreign Entities.”

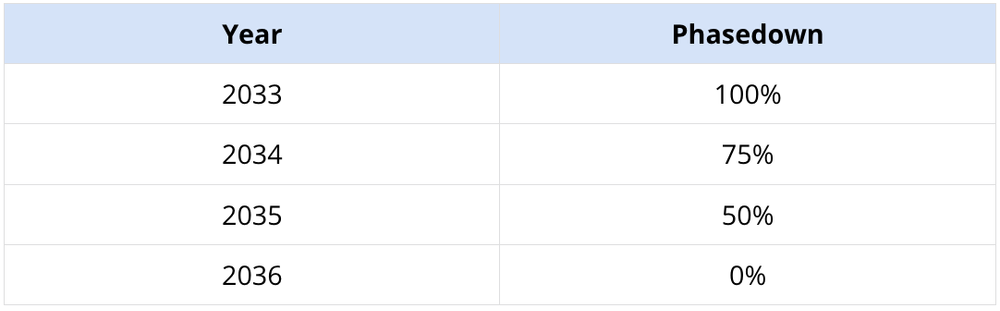

Other Credits – Nuclear, geothermal, and clean‑hydrogen projects, remain on the original statutory timeline, phasing down after 2032:

Medicaid Reforms

Community Engagement Requirements (Section 71119)

Requires 80 hours/month of work or community engagement for adults enrolled in Medicaid expansion aged 19–64.

- States must implement by Jan 1, 2027 but can implement earlier.

- Includes exemptions such as parents with children under 14, pregnant individuals, and disabled veterans.

- States may request non-renewable implementation delay through Dec 31, 2028.

Provider Taxes (Section 71115)

Reduces “hold harmless” threshold:

- For expansion states, phased down from 5.5% in FY2028 to 3.5% in FY2032.

- Nursing/intermediate care facilities excluded.

- Non-expansion states may retain existing approved taxes.

State Directed Payments (Section 71116)

Caps Medicaid state-directed payments tied to managed care contracts:

- Expansion states: 100% of Medicare rates

- Non-expansion states: 110% of Medicare rates

- Existing payments grandfathered, phased down by 10% annually starting Jan 1, 2028.

Rural Health Transformation Program (Section 71401)

Provides $50 billion over FY2026–FY2030 to states to address rural health and hospital needs. 50% distributed equally among approved states; 50% allocated based on rural population, rural provider capacity, and hospital stress.

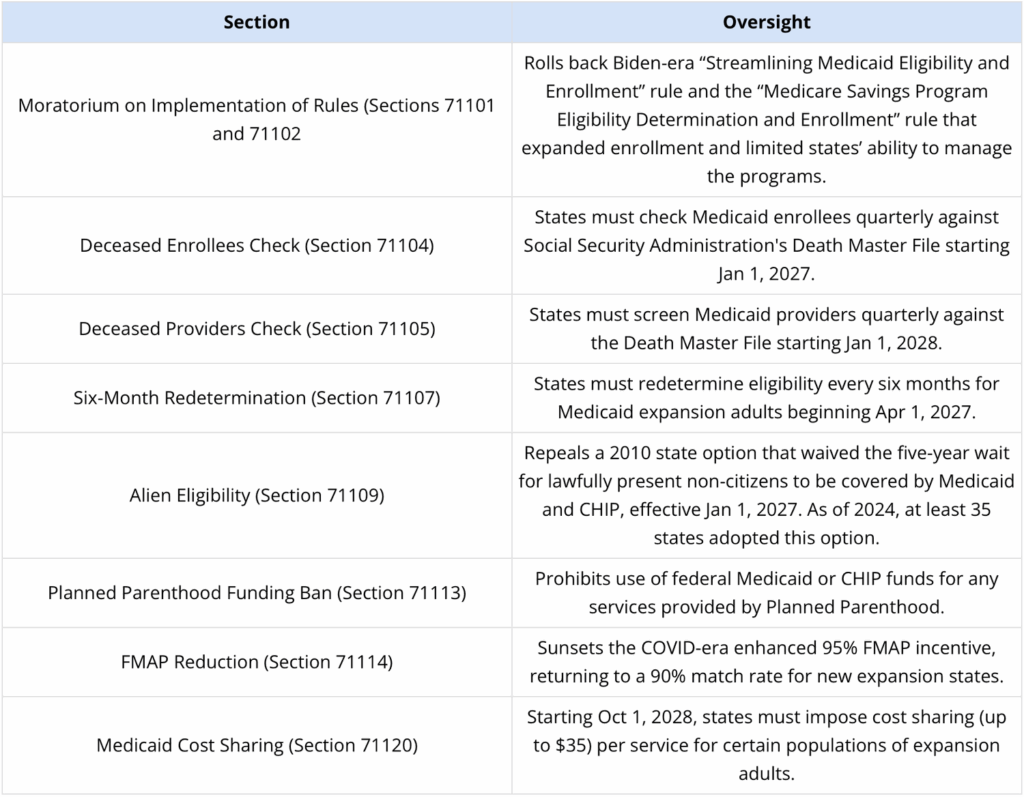

Additional Oversight to Address Waste and Fraud

Border State and Local Government Assistance

State and Local Assistance (Section 90005)

- $10B through FY2034 for State Border Security Reinforcement Fund for barriers, buoys, relocation, interdiction or to reimburse related expenses post Jan 20, 2021. No new immigration enforcement authority granted to states.

- $2.575B of state and local FEMA grants through FY2029 which includes funds for special events, $500M for unmanned aircraft systems tracking and detection, and $450M for border enforcement.

Tax Credit for Education Scholarships

This provision, debated for decades, was significantly shaped during the Senate process. In particular, a key “opt-in” requirement was added in the Senate after the Senate parliamentarian objected to earlier language, making state participation a conscious choice by governors or state officials.

How the New Tax Credit Works

Here’s what sets this new program apart: beginning with the 2027 tax year, any eligible taxpayer can donate up to $1,700 each year to a certified nonprofit scholarship granting organization and get every dollar back as a federal tax credit, a direct reduction off their tax bill, not just a deduction from income.

Scholarship nonprofits then award the funds as K-12 education scholarships, covering not just private school tuition, but books, technology, and potentially a range of other educational expenses (including for public school students and homeschoolers, though some details remain to be clarified in forthcoming guidance). The value of each child’s scholarship will vary depending on how much money the nonprofit is able to raise. Notably, families can combine or stack this federal benefit with state-level school choice programs where they exist, a major boost, given that state awards often don’t cover the full cost of tuition, which now averages around $13,000 nationally.

Who Participates and How Many?

Eligibility for scholarships is broad: households earning up to 300% of their area’s median income can apply. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, the program could cost $3 billion to $4 billion per year, but because the final law has no national cap, the ultimate cost will depend on how many Americans claim the credit. If participation is high, millions of Americans could use the credit, an outcome that would have major fiscal impact. Realistically, actual uptake will depend on donor interest and how many states decide to opt in.

State Decision Points

Governors or designated state officials responsible for federal tax benefit elections must decide by January 1, 2027, whether to opt in and must certify eligible scholarship organizations. For the state leaders, it’s worth noting: this program involves no cost or financial risk to states, participation is purely voluntary, but states that opt out will close the door on the new scholarships for their families.

What’s Next for State Leaders

Implementation starts now. Federal agencies, led by the Secretary of the Treasury, will be developing regulations in the coming months. Policy leaders, state officials, and education organizations should begin closely monitoring state-level opt-in debates and engaging with policymakers to ensure their state is positioned to benefit.

For states that opt in, it will be critical to track the process of scholarship group certification, advocating for a transparent and fair system for selecting eligible scholarship granting organizations. Education efforts should also start early, so that by the time the tax benefit takes effect, taxpayers are aware of the direct, dollar-for-dollar federal credit available for contributions.

In participating states with existing scholarship programs, leaders should also prepare for both the opportunities and potential challenges of “stacking” federal and state dollars; coordinating benefits to maximize support for families, while ensuring compliance and avoiding administrative confusion.

State and Local Tax (SALT) Deduction

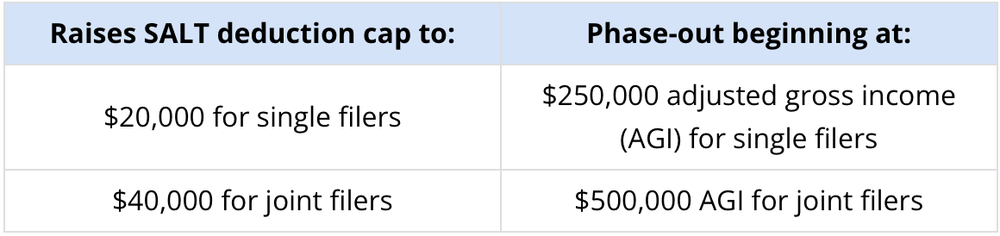

Limitations on Individual Deductions for State and Local Taxes (Section 70120)

In 2025:

This cap will rise to $40,400 in 2026 and by one percent thereafter.

In 2030, the cap will revert to $10,000.